In different cultures, specific foods often mark the arrival of a certain time of year or of some joyous festival, adding to the anticipation of the coming day. For example, Americans enjoy roast chicken on Christmas, the Spanish eat grapes on New Year’s Eve, while Japanese celebrate the day by having soba noodles. This shows the important role these foods play in festivals and their implied cultural meanings in different countries.

In Taiwan, food is always a part of end-of-year gatherings, with various sweet and salty cakes made of rice figuring prominently during the Lunar New Year festivities. Most of the dishes enjoyed at this time of year embody the hope for abundance in the days to come.

We went to Donghu Market (東湖市場) in Neihu District to talk to the woman behind “Know-Sticky Oil Rice (采緹油飯),” an eatery which has been in business there for over three decades. The owner, Lin Tsai-ti (林采緹), introduces us to the special rice-based dishes for the Spring Festival and Lunar New Year celebrations, and tells us about the inseparable links between these sweet and salty flavors and the local culture, as well as the symbols of good fortune and blessings for a prosperous future. (You might also like: Traditional Markets: Extraordinary Witnesses of Ordinary Times)

Auspicious Meanings Behind Rice-Based Dishes

Lin, like a kind aunt who always brings food to share during the holidays, first talks about Taiwan’s various ritual foods locals indulge in during the cold winter months, starting from eating tangyuan during the Winter Solstice, which marks the beginning of the year-end rituals of sending out the old and welcoming in the new. “This symbolizes aging and means blessing and reunion,” she says. (Read more: Handmade Tangyuan — Every One a Treasure onto Its Own)

Next, on the 16th day of the twelfth lunar month, also known as weiya (尾牙), people usually prepare mochi to worship the local Earth God or Tudi Gong as he is known locally, hoping that this sticky dessert made of glutinous rice will bring wealth and good luck. People in Taipei also eat guabao (刈包) on the day, as the bun stuffed with pork belly and pickled vegetables resembles a purse full of money.

When the Lunar New Year officially begins on the 30th day of the twelfth month of the lunar calendar, every family prepares sweet and savory New Year rice cakes, such as sweetened sticky-rice cakes (niengao, 年糕), steamed sponge cakes (songgao, 鬆糕), steamed rice-flour cupcakes (fagao, 發糕), and steamed radish cakes (luobogao, 蘿蔔糕), to worship their ancestors and gods and to pray for peace in all seasons. The Chinese word for cake “糕 (gao)” has the same pronunciation of “高 (gao, high in position),” which means to reach a higher stage in one’s life and work, therefore symbolizing good fortune and the hope of prosperity for the family. (Read also: Hoshing Pastry Shop: Unrolling over 70 Years of Delicious Treats)

The 9th day of the first month in the lunar calendar is the day of the “Birth of the Lord of Heaven (天公生).” In the folk religion of the Han culture, the Jade Emperor (玉皇大帝), known also as the “Lord of Heaven (天公),” is believed to be the god who manages everything in the universe. Therefore, on his birthday, people prepare desserts with fillings wrapped with glutinous rice that is dyed red to celebrate. These include red turtle cake (anggugui, 紅龜粿) in the shape of a tortoise, which is a metaphor for longevity and good luck. There are also qiana (粁仔), which refers to the shape of ancient coins, representing money rolling in.

The 15th day of the Lunar New Year, which is also the first full moon, is the day of the Lantern Festival (元宵節). It is usually regarded as the end of the Lunar New Year. On this night, when spring returns, lights and decorations are displayed everywhere. When people go out to watch the moon and lanterns, they also eat yuanxiao (元宵), which are similar to tangyuan but different in how they are made, as the New Year celebrations draw to an end with the symbolic meaning of reunion and safety. (Read more: Lantern Festivals, Rice Dumplings, and Other Taiwanese Traditions)

Behind the Taste of Sweet and Savory

Each of the sweet and savory rice dishes made for different festivals has its own production techniques, cultural significance, and conventions.

Desserts such as tangyuan and rice cakes are usually made from round glutinous rice, which is ground into powder before being mixed with water to form dough. A little bit of it is taken to be boiled to form banniang (粄娘) or guiyin (粿引), which is a piece of gluey dough that is to be incorporated into the original glutinous rice dough to increase its stickiness. Then, depending on what is required for the subsequent processing, it is colored an auspicious and celebratory red, or mixed with processed mugwort. After that, various sweet or savory fillings are inserted into the dough.

Lin shows us how to insert sweet red bean filling and savory shredded radish into the glutinous rice dough before sealing the opening and placing the dough on an oiled wooden pastry mold, then lightly patting the dough to flatten it. Then, the mold is carefully removed to produce a red turtle cake, symbolizing longevity.

Introducing the wooden pastry mold in her hand, she says, “We specially ordered it from an old store on Dihua Street, and all of these wooden patterns are hand-carved to make a deep and beautiful print.” The wooden mold features not only a turtle shape, but also a peach, representing good luck on the other side. On the edges, there are three bronze coin shapes, allowing people to make different imprints on the rice cake, depending on what their needs are. “A good wooden mold will last forever, and many old bakeries have heirloom molds,” says Lin. However, as the number of businesses producing handmade products dwindles, rice cakes with imprinted patterns are becoming rarer and rarer.

When the imprinting is done, the cakes can then be placed into the steamer to be steamed for about 25 to 30 minutes. “We have to take care of the heat during the process though. Too high a heat can cause the rice dough to collapse and flatten out,” Lin remarks.

Lin also explains how steamed sponge cakes, symbolizing good fortune, are made. First, grind rice of the Penglai (蓬萊) or Zailai (在來) variety into pulp before adding brown sugar or caster sugar. Then, steam the rice pulp over high heat for it to rise naturally and blossom into the appearance of a flower. On the other hand, the soft and sweet New Year rice cakes are made by slowly mixing glutinous rice flour with sugar and oil, and then steaming the mixture over high heat for three to four hours. These are important desserts used for offerings during the Lunar New Year. (More about Taiwanese rice: Taipei: City of a Hundred Grains)

“In Taiwan, there are almost always different foods corresponding to different seasons and times of the year, so we are always looking forward to the upcoming festivals,” Lin says. She learned to make cakes that are linked to the rituals of different seasons and folk beliefs by hand when she was young, and has been selling them in markets so that Taipei residents can also feel the changing seasons and the blessings of heaven.

Taboos Related to the Festive Dishes

Lin shares that in the past, when people made Lunar New Year cakes, there were always some traditional taboos to be aware of. People usually consider that if New Year rice cakes, which are made only once a year, are not made well, things in the year ahead will not go your way. Therefore, several rules are followed to ensure everything goes according to plan.

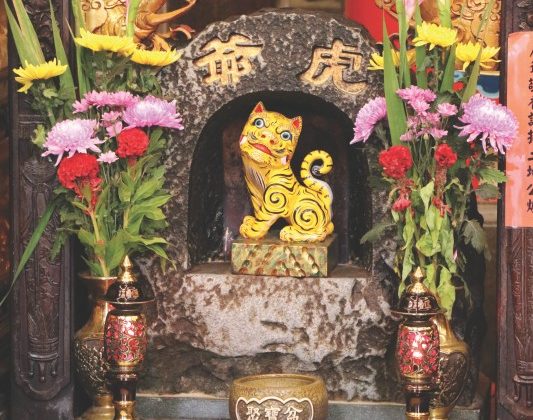

For example, when steaming sponge cakes, no one should ask whether they are done when approaching the stove. Neither should people argue or scold children around it. Otherwise, the cakes will not be fully steamed. Until today, some conservative families are very serious and cautious when making New Year rice cakes. Some even say that people born in the Year of the Tiger should keep away to ensure the success of cake, since the tiger in the Chinese zodiac is often considered intimidating.

However, Lin also explains that technology was not well developed in the past, so it was not possible to control the temperature and heat as easily as it is today. That is why it was necessary to exclude any and all negativity as much as possible that may (or may not) have affected the production process. Since many of these past difficulties can be overcome in modern times, lots of myths and folklores that carried much weight in times past are no longer as relevant in the modern context. Lin herself was actually born in the Year of the Tiger, but has been making rice cakes for over three decades.

Ways to Enjoy Sweet and Savory Rice Cakes

Steamed Sponge Cake

The flavor of this fluffy and slightly sticky cake most commonly seen in Taiwan is brown sugar, but recently many other variations like whole grain or pumpkin are becoming available.

Sweet New Year Rice Cake

This cake is often sweet and sometimes mixed with red beans and cheese. It is usually sliced and pan-fried or dredged and deep- fried, and can also be served as an after-meal dessert during the Lunar New Year holidays.

Red Turtle Cake

Printed or shaped like a turtle, this cake is often stuffed with sweet fillings such as red bean paste and peanuts paste. Shredded radish is also a common savory flavor.

Tangyuan

This ball-shaped dessert can be eaten without fillings and with sweet soup. There are also those with meat fillings for a savory taste and others with sesame or peanut fillings for a sweet taste. Nowadays, they are also available with novel fillings such as chocolate, Matcha, and custard cream.

Steamed Radish Cake

Commonly seen in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and around Southeast Asia, steamed radish cake is not only a New Year dish, but also an everyday staple. It is often pan- fried and served in local breakfast shops in Taiwan and can also be found at dim sum restaurants.

Savory New Year Rice Cake

Mixed with stir-fried shallots and minced pork, this kind of New Year cake tastes both savory and sweet, forming a unique, old- fashioned Taiwanese flavor. It can be eaten on its own or pan-fried with an egg wrap.

| KNOW-STICKY OIL RICE |

| ADD 21-1, Ln. 315, Ankang Rd., Neihu Dist. HOURS Please check the opening hours via website before visiting WEBSITE www.facebook.com/tsai.ti.food/ |

Author Elisa Cohen

Photographer Samil Kuo

This article is reproduced under the permission of TAIPEI. Original content can be found on the website of Taipei Travel Net (www.travel.taipei/en).